The fleet flagged under EU Member States accounts for approximately 12% of the global fleet, with 15 096 vessels registered as of the second quarter of 2024. In terms of gross tonnage (GT), the EU fleet constitutes over 14% of the global fleet, amounting to 236.3 million GT, while it represents approximately 13% in terms of deadweight, totalling 298.8 million tonnes.

As of the second quarter of 2024, the fleet registered under EU Member States includes a diverse range of vessel types, both in absolute numbers and percentage. It accounts for nearly 27% of the global RoPax fleet (transport of passengers and vehicles, 912 ships), almost 23% of the world's passenger vessels (1 226) and more than 18% of the global containership fleet. In absolute terms, the most prevalent ship type was fishing vessels (2 540), followed by tugs/dredgers (2 007) and general cargo ships (1 468).

The EU's shipbuilding industry comprises approximately 150 major shipyards engaged in the construction of various types of vessels, both civilian and naval, as well as platforms and other maritime equipment. According to the European Maritime Safety Agency, in 2023, around one in eleven ships was built in an EU shipyard, with the majority consisting of tugs/dredgers (38), fishing vessels (29), general cargo ships (29), and passenger ships (26).

Average age of ships varies notably by the type, with FPSOs (Floating Production, Storage, and Offloading units), passenger ships and refrigerated cargo recording more than 30 years (33.2, 30.5 and 30.1, respectively).

At the opposite end, chemical tankers, containerships, bulk carriers and liquefied gas tankers have been built on average less than 15 years ago (14.1, 13.4, 12.4 and 10, respectively). Age is intrinsically related to end of life. In 2023, a total of 437 ships were recycled worldwide. Among them, 22 were dismantled at EU ship recycling facilities, while four EU-flagged vessels were scrapped outside the EU.

Shipbuilding and repair includes the following sub-sectors:

- Shipbuilding: building of ships and floating structures; building of pleasure and sporting boats; repair and maintenance of ships and boats.

- Equipment and machinery: manufacture of cordage, rope, twine and netting; manufacture of textiles other than apparel; manufacture of sport goods; manufacture of engines and turbines (except aircraft), and manufacture of instruments for measuring, testing and navigation.

Size of the EU Shipbuilding and repair sector

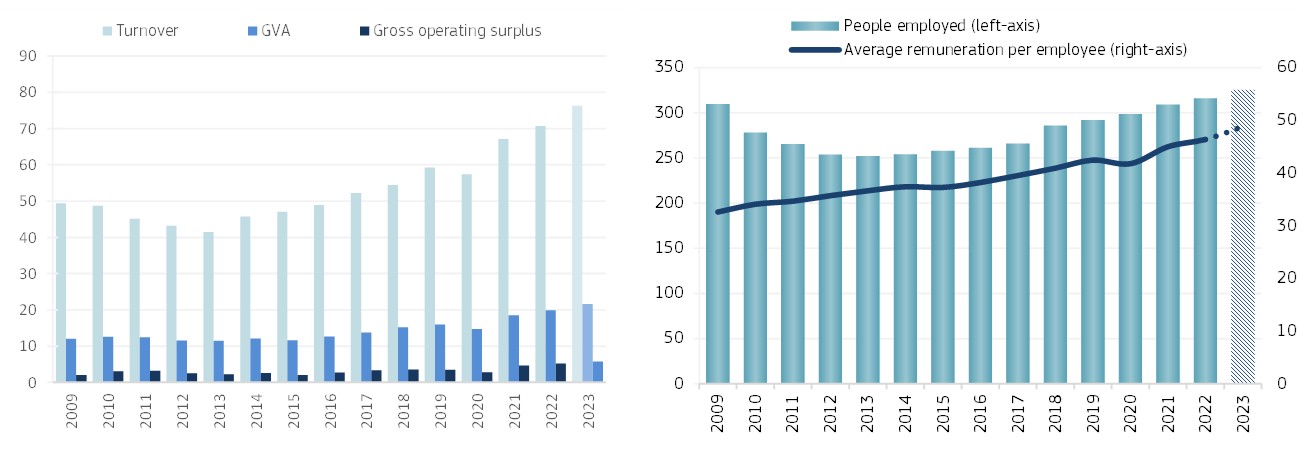

The sector generated a GVA of EUR 19.9 billion in 2022, a 7% increase compared to 2021. Gross profit, at EUR 5.2 billion increased by 14% on the previous year. The turnover reported for 2022 was EUR 70.7 billion, recording a 5% increase on the previous year (Figure 1).

In 2022, about 316 000 persons were directly employed in the sector (2% increase on 2021), and the annual average wage was estimated at EUR 46 400, up 3% compared to 2021.

Estimates for 2023 indicate an increase in GVA, gross profit and turnover between 8-10%. Also, an increase in persons employed and average remuneration is estimated between 3-5%.

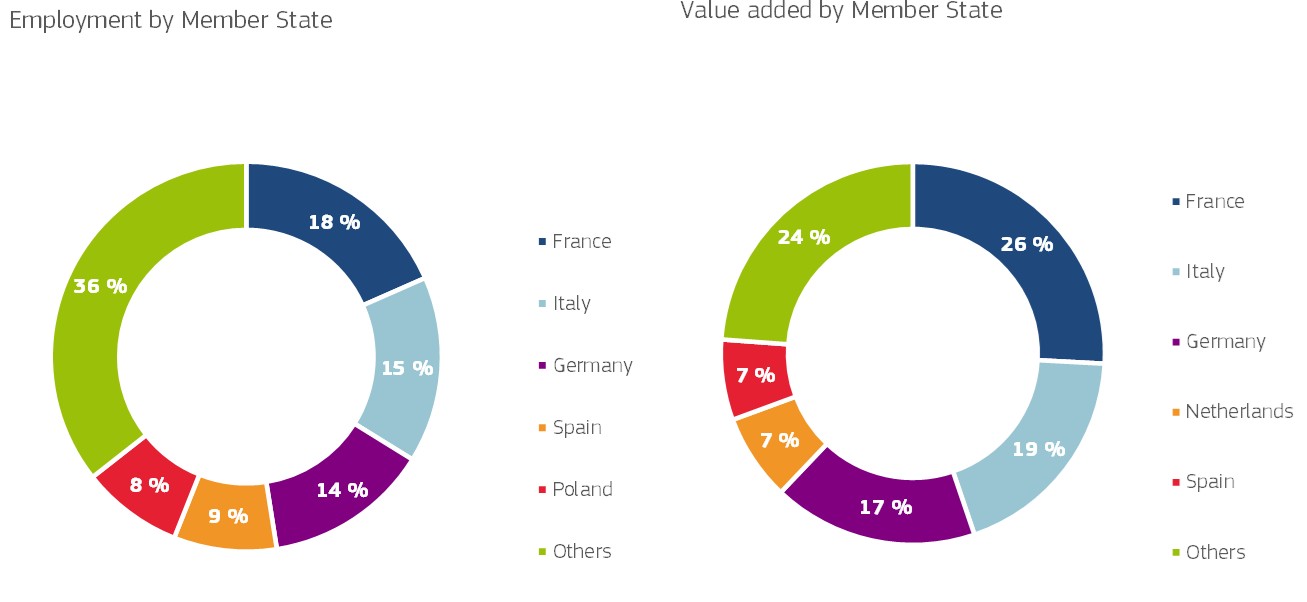

France leads employment within Shipbuilding and repair, contributing with 18% of the jobs, followed by Italy and Germany (15%). In terms of GVA, France records 26% of the Members States’ GVA, followed by Italy (19%) and Germany (17%) (Figure 2).

Shipbuilding generated about 85% of the jobs and about 79% of the sector’s GVA; while Equipment and machinery generated the remaining 15% of jobs and 21% of GVA.

For more detailed economic and social data, please consult the dashboard on the Blue Economy Indicators.

The European shipbuilding industry [1] experienced a surge in 2023, with a total of 101 new orders being placed at European shipyards. This represents a 9% increase over the previous year, driven primarily by a surge in demand for dry cargo vessels, which accounted for 71 of the new orders, as well as cruise ships, with 11 new orders recorded. This growth is second to the Chinese orders (+29% on a year-to-year basis), which confirms its position as the top shipbuilding nation globally. Indeed, China recorded a market share for new orders of 63.2% (+11.7% from previous year), whilst European market share increased very marginally to 5.6% (from 5.4%).

[1]The figures are based on the BRS Group, 2024 – Shipping and Shipbuilding Markets – Annual Review 2024 edition. The European market under examination includes the following countries listed by decreasing number of cumulative orders on the book: Italy, France, Germany, Finland, Turkey, the Netherlands, Poland, Croatia, Spain, Romania, Azerbaijan, Portugal, Ukraine, UK, Greece and Norway.

These shares testify the staggering pace of the Chinese shipbuilding industry, which is taking orders once placed on different markets. Other major shipbuilding countries continue experiencing a decline in new orders: South Korea recorded -19% whilst Japan a staggering -31%, and their respective market shares declined by 4.1% and 6.9%.

Italy counted the highest number of orders in 2023 with more than 2.7 million GT (total of 351 ships), followed by France with 1.6 million GT (total of10 ships). This is mainly due to Fincantieri (Italy), which is the largest cruise shipbuilder in the world, with 30 cruise ships on order (roughly 45% of the global cruise ship orderbook), and to Chantiers de l’Atlantique, which has 10 cruise ships on the orderbook.

Figure 3 compares the evolution of GDP and new ship orders in Europe. Although a decreasing trend can be discerned from 2018 to 2020, there is not a strong correlation between these two indicators overall (0.29).

There are some factors that are currently influencing the shipbuilding and repair sector and are expected to significantly impact it in the near future. The geopolitical instability, resulting from Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, has affected the shipbuilding industry. Uncertainties surrounding shipping routes in the region have led some companies to postpone long-term investment decisions. One direct consequence has been a surge in global demand for LNG vessels, driven by shifts in energy trade flows—while Russia exports more fuel oil to Asia, Europe has increasingly relied on LNG carriers for gas imports instead of pipeline deliveries from Russia. The geopolitical instability has also led the European Commission to publish the Joint White Paper European Defence – Readiness 2030, which will have most likely a positive impact on the shipbuilding industry. Finally, the roadmap to a greener industry affects the shipbuilding and retrofitting of ships but also the disposal at the end of life.

The Joint White Paper for European Defence Readiness 2030 calls for “a massive increase in European defence spending” to support the development of a stronger, more resilient defence industrial base and an ecosystem of technological innovation for the defence industries. The document identifies seven priority capability areas, including some relevant to the blue economy, such as EU-wide network of seaports that facilitate the seamless and fast transport of troops and military equipment across the EU and partner countries (i.e. military mobility), and strategic enablers and critical infrastructure protection in the maritime domain.

In 2024, total defence spending by EU Member States is expected to exceed EUR 326 billion, marking a more than 30% increase compared to 2021 and reaching a record 1.9% of EU GDP. Between 2021 and 2027, real-term growth is projected to surpass EUR 100 billion, exceeding previous estimates. Investments in research, development, and procurement of new defence capabilities are also set to rise significantly, from approximately EUR 59 billion in 2021 to EUR 102 billion in 2024.

The naval sector plays a crucial role in EU defence capabilities, offering a wide array of vessels, from aircraft carriers to nuclear submarines. The EU naval vessels market is highly consolidated, with leading companies such as Navantia S.A. S.M.E., Naval Group, FINCANTIERI S.p.A., ThyssenKrupp AG, SAAB Kockums, Damen Naval, Naval Vessels Lürssen dominating the industry. These key players operate multiple shipbuilding yards dedicated to the development of naval vessels. Together, they have joined forces for the SEA Defence project, aimed at preserving the competitiveness of the European naval industry by focusing on emerging technologies on naval capabilities and increasing operability among European navies.

In 2023, members of the Aerospace, Security, and Defence Industries Association of Europe reported that the sector generated EUR 37.9 billion in revenue, accounting for 24% of total European defence revenue. This marks a 17.7% increase compared to 2022. Similar estimates are reported by Mordor Intelligence, which estimates the value of the European naval vessels market at EUR 36 billion in 2025 with a projection at EUR 58 billion by 2030, following a CAGR of 10.21%.

The increase in defence spending, aligned with the Joint White Paper European Defence – Readiness 2030, is expected to drive the sector's growth in the medium to long term.

Developing zero-emission vessels requires a lifecycle approach to assess key environmental impacts across all stages, including design, construction, operation, and disposal. Shipyards, as industrial production facilities, rely on materials and energy-intensive processes such as cutting, bending, welding, sandblasting, painting, and coating. These processes are complex and contribute significantly to environmental and climate impacts. The shipbuilding industry is responsible for approximately 4-8% of the total life cycle CO₂ emissions of diesel-powered ships and accounts for 29% of carbon monoxide emissions. Additionally, it generates volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which contribute to the formation of tropospheric ozone, posing risks to both human health and the environment. Although the greatest potential for reducing a vessel’s lifetime emissions lies in the fuels used during operation, the construction phase plays a crucial role in determining a vessel’s embodied energy and overall environmental footprint.

The International Maritime Organisation’s Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) are pushing shipbuilders to create more energy-efficient vessels that meet strict emissions targets. Industry 4.0 technologies, like robotic welding and automated cutting, improve shipyard efficiency and reduce GHG emissions. Additionally, integrating renewable energy, microgrids, and battery storage can lower the carbon footprint, though space limitations and high costs remain challenges Using sustainable materials like eco-friendly composites and green steel also enhances environmental performance, though green steel production is largely concentrated in Europe. Green Supply Chain Management is crucial in shipbuilding, where 60–80% of a vessel’s value is outsourced, impacting its environmental footprint.

Finally, responsible recycling at a ship’s end-of-life is essential, with 1.3–2.1 million LDT of scrap produced annually in the EU. Between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2021, EU Member States and Norway reported a total of 90 ships that received a ready-for-recycling certificate, confirming they met environmental and safety standards for dismantling and recycling in EU-approved yards. Of these, 41 vessels completed the recycling process, which took place in seven facilities, with Turkey handling the largest share (50%). In 2022, vessels flagged in EU Member States represented 13.2% of the global fleet, but only 7% of end-of-life vessels recycled were flagged under an EU Member State at the time of recycling. This indicates that the goal of ensuring safe and environmentally sound recycling, as outlined by EU legislation, is still challenged by the practice of re-flagging. This could also reflect recent changes in global shipping policies, which now prioritise the use of safe and environmentally sound recycling facilities for end-of-life vessels.

These elements contribute to the greening of the sector, in line with the EU strategy of transitioning towards a green industry. Projects funded by the EU, such as EcoShipYard, contribute to this objective, by developing solutions to reduce the environmental impact of shipyards, increase energy efficiency, optimise operations and measure and reduce non-operational impacts.

As new regulations, such as FuelEU Maritime, take effect, many vessels risk non-compliance unless significant improvements are made. The shipping industry faces a complex decision between retrofitting existing vessels, investing in new ships, and securing green fuel supplies, all of which require substantial capital investment. Retrofitting has gained strategic and economic importance as a key solution for transforming high-emission ships into climate-friendly vessels, ensuring compliance with international and EU environmental regulations.

Retrofitting involves upgrading ships to improve their environmental performance, particularly given the significant number of older vessels contributing to global emissions. Traditional ship designs and propulsion systems release large amounts of sulphur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon dioxide (CO2), and particulate matter16. Retrofitting solutions—such as exhaust gas cleaning systems (scrubbers), alternative fuel systems (LNG, hydrogen, ammonia), and energy efficiency enhancements (air lubrication systems, hull coatings)—can significantly lower emissions and ensure compliance with IMO 2020 sulphur cap and CII requirements. Beyond compliance, these technologies also improve fuel efficiency, reduce operational costs, and enhance the competitiveness of shipping companies.

Among all retrofit options, the most impactful from both shipyard and GHG emissions perspectives is the installation of a new engine and fuel system capable of running on alternative fuels like methanol, ammonia, or hydrogen. However, engine replacement is a technically complex process requiring skilled labour, specialised facilities, and significant investments. It also involves integrating new fuel systems and tanks, which can be challenging and costly depending on the fuel type. As an alternative, ships can be supplemented with battery systems to reduce diesel dependency. Other retrofitting measures include expanding shore power capabilities to reduce emissions while at berth and exploring wind-assisted propulsion to cut fuel consumption.

Despite its potential, eco-friendly retrofitting is not without risks. While European Ship Maintenance, Repair and Conversion (SMRC) shipyards and their supply chains are well-positioned to benefit from retrofitting activities, technological aspects (e.g. feasibility, efficiency, safety, and longevity of new systems), environmental concerns (e.g. lifecycle impact of retrofitting solutions), economic factors (e.g. high upfront costs, uncertain long-term financial returns)17, social elements (e.g. shortage of skilled labour) as well as evolving regulations and unfair competition from subsidised shipyards in other regions18 are key challenges that the sector faces.

For more information visit the section on Shipbuilding and repair within the EU Blue Economy Observatory.