The marine extractive industry is a large sector that specialises in the commercial exploitation of non-living resources extracted from the oceans, the seabed and beneath the seafloor. These include hydrocarbons, minerals, metals, and water. This industry is divided into several segments, each with unique characteristics and extraction methods. Globally, the top extracting countries include China - a major player in offshore oil and gas and marine mining, with significant investments in the South China Sea and beyond; the United States - a leading producer of offshore oil and gas, with major operations in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska; Australia - a significant producer of marine minerals, including iron ore, copper, and gold, with major operations off the coast of Western Australia; Norway - a leading producer of offshore oil and gas, with major operations in the North Sea; and the United Arab Emirates - the country with the largest desalination installed capacity.

Marine non-living resources have been a significant sector in the EU Blue Economy for many years. Most of the EU’s domestic oil and gas is extracted offshore. Out of 16 264 kilotonnes of oil equivalent (ktoe) extracted from EU waters in 2022, 69 % was gas and 31 % oil. 80% of total EU offshore production was extracted in the North Sea and Atlantic by the Netherlands (7 812 ktoe), Denmark (4 435 ktoe) and Germany (755 ktoe). 12% was extracted in the Mediterranean (mainly by Italy with 1872 ktoe), 5.7% in the Black Sea (mainly Romania) and 1.6% in the Baltic Sea (by Poland). As required by the Offshore Safety Directive [1] the 14 Member States active in the EU offshore oil and gas extractive industry reported a total of 311 offshore oil and gas installations in EU waters in 2022. 53% of these offshore installations (164) were in the Mediterranean Sea, 43% (135) in the North Sea and Atlantic, 3% (8) in the Black Sea and 1% (4) in the Baltic Sea. 18 % of these installations were manned, fixed platforms and 80% were normally unattended installations[2].

Over the past decade, the mature offshore oil and gas sector has experienced a decline, following the ambitious EU decarbonisation goals and net-zero emission targets. The number of active platforms decreased by 36 units in 2022, and total EU offshore oil and gas production dropped from 18 187 ktoe in 2021 to 16 264 ktoe in 2022 (-11%)[3]. As the industry is engaged in this transition, new opportunities for sustainable marine mining are gradually opening. Oceanographic research can facilitate the sustainable exploitation of mineral resources from the seafloor, by providing critical data and insights on its environmental, social, and economic implications, as well as approaches to protect and restore vulnerable marine ecosystems.

The Marine non-living resources sector comprises three main subsectors:

- Oil and gas: Extraction of crude petroleum, Extraction of natural gas, Support activities;

- Other minerals: Operation of gravel and sand pits; mining of clays and kaolin; it also includes extraction of salt.

- Desalination: extraction of seawater and brackish water to produce desalinated water for civil, agriculture and industrial uses.

Desalination is now included as a subsector, rather than presented as a separate, emerging sector of the blue economy. This enables a more comprehensive coverage of the various segments of the industry extracting and commercially exploiting abiotic resources from our seas and ocean. Methodological challenges remain in isolating and quantifying the socio-economic performance of desalination from aggregated and undifferentiated SBS statistics. Nonetheless, the report can provide estimates of desalination turnover, GVA and employment using complementary data sources. It should be noted that desalination and other marine extractive activities can cause significant environmental impacts in terms of both ecosystem disturbance and impingements and entrainment of marine life (e.g. fish, algae, and larvae). Minimising and managing these environmental impacts is crucial for the blue economy’s sustainability transition.

In 2022, the GVA generated by the sector amounted to EUR 10.7 billion, up from EUR 4.7 billion the year earlier (2021). This increase, boosted by a similar year-on-year increase in turnover – reaching EUR 29.6 billion in 2022, up from EUR 15 billion in 2021 – is the result of geo-political considerations following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. This led to a number of installations designated for decommissioning to resume operation, and increase the security of energy supply in the EU[5]. The good performance of the sector in 2022 is further testified by a 2.6-fold increase in profits, which reached EUR 9.5 billion, up from EUR 3.6 billion in 2021.

Apart from the short-term effects caused by the geo-political situation, the oil and gas subsector kept shrinking, as testified by the preliminary, estimated figures for 2023, which show less than 7 000 persons employed in total, i.e. the lowest value on record since 2009 with more than 800 job losses from 2022. A similar downward trend can be observed for average personnel costs, which decreased by 6% compared to 2022, explaining the continued, slight increase in average remuneration per employee (Figure 1).

Driven by the oil and gas decline, the sector’s turnover has been falling sharply between 2012 and 2017, to then fluctuate between EUR 14 billion and EUR 15 billion until 2021, except for the further decrease due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, the sector’s workforce was less than 43% of its equivalent in 2009, and turnover was about 26% of the highest value it reached in 2012. In 2022, the Marine non-living resources sector accounted for 0.3% of the jobs, 4.2% of the GVA and 4.3% of the profits of the entire EU Blue Economy.

Spain, Denmark, the Netherlands, Romania and Italy (in this order) have the highest employment in the marine non-living resources sector, with 82.1% of the sectoral workforce. The Netherlands and Denmark together produce by far the largest share of the sector’s GVA (84.2%), followed by Italy (8.3%) and Spain (4%). (Figure 2).

Employment: The EU Marine non-living resources sector employed less than 17 thousand persons in 2022, compared to nearly 37 thousand in 2009. The industry is among the most affected by the transition to sustainability in the energy sector, hence the strong decline in the workforce in line with global trends. 45% of the sector’s workforce was employed in desalination, followed by 27% in support activities for the oil and gas industry, 13% in the extraction of natural gas, and 6% in oil extraction.

Gross value added: 69% of the sector’s GVA was generated by the gas extractive industry (EUR 7.4 billion in 2022), followed by the extraction of crude oil (17%, or EUR 1.7 billion in 2022). Oil and gas support activities contributed another 7% to the sector’s GVA, while desalination generated only 6% (EUR 611 million) in 2022.

The overall market performance of the marine non-living resources sector over the past few years can be explained by several factors, such as the implications of relevant EU policies and regulations, the impact of exogenous shocks (e.g. COVID-19, conflicts, trade disruptions, etc.), and the effects of changes in energy prices, production costs and tariffs on demand and productivity of the EU marine extractive industry. These factors may have affected its different sub-sectors in different ways.

Oil extraction: Despite the growing role of gas and the ongoing transition to renewable sources, oil continues to play an instrumental role in the EU energy economy, particularly in sectors such as transport, the petrochemical industry and port logistics chains. However, structural data and projections by official bodies confirm a sustained decline in the weight of crude oil within the European energy system.

Crude oil production in the EU reached an all-time low in 2022: 16.3 million tonnes, compared to a peak of 41.7 million tonnes in 2004, representing a cumulative fall of more than 60%[6]. Italy (4.5 million tonnes), Denmark (3.2 million tonnes) and Romania (3.0 million tonnes) account for most of the production, mainly in offshore fields (See Figure 3). The sustained decline is due to both resource depletion and a reduction in exploratory investment, in line with climate targets and environmental, social and governance (ESG) policies. Crude oil production in the EU is expected to continue declining, focusing on extending the life of mature fields, without significant new offshore developments planned for the 2025–2028 period[7].

The EU's energy dependence on oil and its derivatives remained high, reaching a record high of 97.7% in 2022. Crude oil imports amounted to 479.6 Mt (+7.4% compared to 2021), although still below the pre-pandemic level (507.2 Mt in 2019). The main suppliers were Russia (88.4 Mt), Norway (54.1 Mt), the United States (48.3 Mt), Iraq (37.2 Mt) and Kazakhstan (36.6 Mt)[8].

The war in Ukraine and the launch of the REPowerEU plan in 2022 significantly altered the pattern of crude oil imports in the European Union. Purchases from Russia fell by 24.6 Mt that year (–21.75%), a decline offset by increased volumes from Saudi Arabia (+11.5 Mt), the United States (+10.7 Mt), and Norway (+10.2 Mt). This diversification has reinforced the role of transatlantic and Mediterranean maritime routes, with logistical impacts on key ports such as Rotterdam, Trieste, Marseille and Algeciras[9].

Gas extraction: Since 2021, gas demand in the EU has decreased by around 15% due to the advance of renewables, electrification of residential heating, and improvements in energy efficiency. Despite this structural decline, gas is still needed as a flexible back-up source for power generation and as an indispensable input in industrial sectors that are difficult to decarbonise, such as chemicals, metallurgy, and cement[10][11]. In 2025, natural gas continues to play a key role in the European energy system, albeit in a scenario marked by a transition to more sustainable sources.

Natural gas reserves in the EU are estimated in 694 billion cubic metres (bcm). 90% of these reserves are held by six Member States (Figure 4): the Netherlands (25%), followed by Romania (21.2%), Poland (15.4%), Germany (10.2%), Italy (8.9%), and Denmark (8.3%)[12].

In August 2024, Eni announced the beginning of gas production from the Argo Cassiopeia field in the Strait of Sicily. With reserves estimated in the range of 10 billion cubic metres of gas, gas extraction from the Argo Cassiopeia field is expected to reach 1.5 billion cubic meters per year. The installation aims to achieve carbon neutrality for Scope 1 and 2 emissions with renewable solar energy[13].

The redesign of the European gas supply system represents one of the most significant structural transformations in the post-2022 period. Following the invasion of Ukraine and the political commitment to gradually reduce dependence on Russian gas, the EU has strengthened its gas infrastructure through strategic projects supported, among others, by the Connecting Europe Facility instrument[14]. Four alternative routes to the Ukrainian transit corridor will be fully operational by 2025, ensuring the continent’s energy supply security[15].

Storage has proven to be a crucial element for absorbing market shocks, mitigating seasonal demand fluctuations, and ensuring supply during winter peak consumption periods. Gas storage reached a level of 96% of total capacity in October 2023, also thanks to the Demand Reduction Regulation, which has been exceeded by most Member States[16].

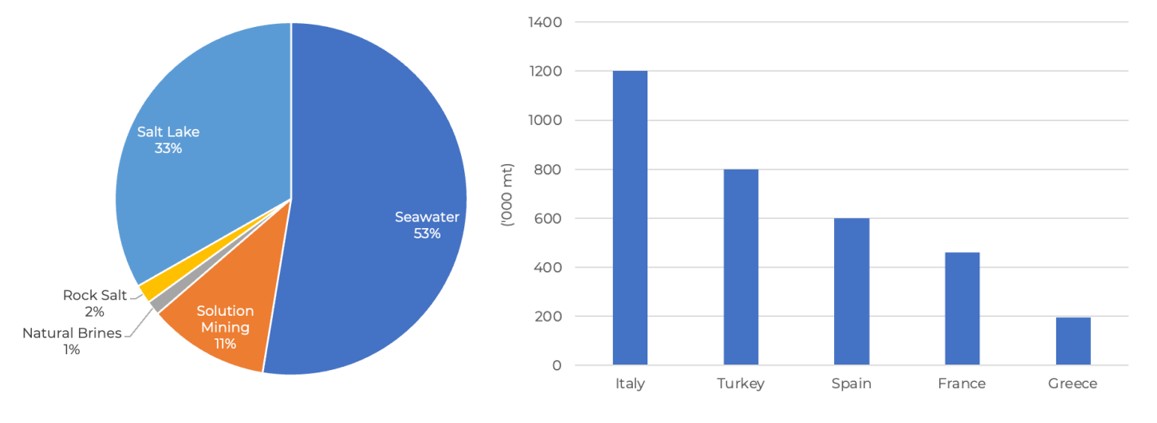

Salt extraction: Sea salt is salt extracted from seawater through evaporation or thermal processes. While solar evaporation is the most common method for sea salt production, thermal processes (like vacuum evaporation) are also used in some regions or specific applications, especially when the climate is unsuitable for solar methods or for higher-purity industrial uses. With a share of 53%, seawater is the largest source of salt production by evaporation in Europe, followed by salt lakes (33%). Production typically takes place in open basins (natural or man-made), salt marshes or marine salt flats alongside the coastline. The crystallization of salt requires a prolonged period of dry weather, as well as wind, sun and warm temperatures. The necessary climatic conditions to produce solar salt are met in Southern Europe, and the production of sea salt takes place along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coast. After a salt crust has formed, excess salty water is removed prior to harvesting the unrefined salt, which then undergoes additional processing steps, such as washing, drying, and sifting[17].

Sea salt represents about 6% of total salt production in Europe. It is produced mainly for food processing, de-icing, and specialty retail markets. Despite its many uses, its application in certain industries is limited, mainly because of high volumes of demand and logistical constraints.

The total sea salt production capacity in the EU is estimated not to exceed 5 million tonnes per year. However, weather conditions dictate actual production volumes. In 2023, sea salt production reached approximately 3 million tonnes[17]. To meet EU demand, mainly for de-icing uses, between 1 and 2 tonnes of sea salt are therefore imported each year from non-EU countries[18].

A total of 25 large-scale industrial companies are active in sea salt production in the EU. Most companies (11) are from Spain. 5 sea salt production companies are from Italy. Other companies are from Croatia, France, Malta, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Portugal and Slovenia. Several companies operate multiple production sites, both in and outside the EU. In addition, many small-scale, manual harvesting plants are present in the EU. France has the largest number of small-scale producers, reaching approximately 600 units. Small-scale production capacity varies considerably. For example, small-scale producers on the French Atlantic coast typically operate between 10 and 100 crystallizers. Their production of coarse salt ranges between 700 kg and 2 tonnes per crystallizer. Production of the more sophisticated, high end blend fleur de sel ranges between 50 kg and 100 kg per crystallizer. This latter production usually accounts for nearly half of their turnover[19].

The sea salt subsector in the EU employs more than 2 200 workers in total, two thirds of which are employed in large-scale industrial facilities. The subsector generated a turnover of EUR 432 million, of which only 11% from small-scale producers[20]. Small-scale salt production generates approximately EUR 60 million in turnover and employs around 850 people[21].

Sea salt production is typically low in energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions, especially if the evaporation process is driven by sun and wind. However, certain components of the production process (especially pumping, maintenance, harvesting, and post-processing like washing and drying) can be energy-intensive, depending on technology and scale, let alone if thermal dryers are used. In addition to energy costs, prospects for market growth are constrained by several factors, such as transportation costs, and the limited availability of suitable production sites near the coast.

Extraction of other minerals: The extraction of minerals from EU seas and seabed is a significant industry, with various activities taking place across the region. The market can be broadly segmented into three main categories: gravel and sand pits, mining of clays, and deep seabed mining for other minerals.

- Gravel and Sand Pits: The extraction of gravel and sand from EU seas is a well-established industry, with many Member States having long histories of offshore aggregate extraction. Most of these operations take place in shallow waters, typically less than 20 meters deep, and are used to supply the construction industry with materials for building and infrastructure projects. The Netherlands, and Denmark are among the largest producers of offshore aggregates in the EU, with the North Sea being a major hub for these activities.

- Mining of Clays: The mining of clays from EU seas is a smaller but still significant industry, with several Member States extracting clays for use in the ceramics, paper, and construction industries. These operations often take place in shallower waters, typically less than 50 meters deep, and are concentrated in areas with suitable geological formations. France and Germany are among the main producers of offshore clays in the EU.

- Deep Seabed Mining: Deep seabed mining for other minerals is a relatively new industry, with several companies exploring the potential for extracting valuable minerals such as copper, zinc, gold, and rare earth elements from the deep seabed. These operations typically take place at much greater depths, often exceeding 1 000 meters, and require specialized equipment and technologies. However, deep seabed mining raises significant environmental and social concerns, including the potential impacts on marine ecosystems, the risk of pollution and habitat destruction, and the need for careful management and regulation of these activities. For these reasons, the Commission has called for a ban on deep-sea mining until gaps in scientific knowledge are properly filled and it can be demonstrated that this activity has no harmful effects. The Commission’s position on deep-sea mining is set out in the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030[22] and in the International Ocean Governance Agenda[23]. The European Parliament has called three times for an international moratorium on deep-sea mining[24].

- Maritime transport and ports: These sectors play a key support role for the oil and gas industry. Not only are they responsible for the logistics of the sector, but they also provide maintenance, and will play a main role in decommissioning stages, requiring greater shore-based facilities. Oil and gas also impact these sectors by establishing exclusion safety zones around their infrastructure and activity zones, impacting transport routes[25]. Also, LNG serves as a transition fuel for vessels, cleaner than diesel and meeting current IMO emission standards. While not a definitive solution, it is helping alleviate carbon emissions while green fuels like e-methanol or e-ammonia reach technological and availability levels that allow their use for full-scale commercial operations.

- Pipelines and cables: the oil and gas industry is one of the main users of pipeline infrastructure. New extractive infrastructure and activities, also for other non-living resources, must consider existing pipelines and cables and ensure that they are not affected.

- Fishing: the extraction of non-living resources has a major impact on fishing activities. During operations and infrastructure decommissioning, fishing vessels must respect at minimum a 500 metre safety zone, with additional areas during the installation of pipelines. Also, operation activities can discharge contaminants in ecosystems, like crude or contaminated water, and the effect on noise and vibration is still under study[26].

- Aquaculture: In spaces with available resources for both sectors, both activities are excluded. Co-location might be a future opportunity for these spaces, although technological and legal barriers must be first addressed, especially in the case of decommissioned structures.

- Offshore energy: While both sectors are competing for suitable space, there is potential for the installation of offshore energies infrastructure in decommissioned structures, and possible synergies with operating ones, providing access to the electrical grid, and maintenance/logistical support.

- Conservation: The sector poses high ecological risks due to possible oil spills, ecological interactions during exploration, and noise pollution. Nevertheless, there is potential to provide protected spaces around the infrastructure, especially decommissioned structures, that can act as artificial reefs,

- Research and innovation: the sector is highly dependent upon new technologies that allow further exploitation of existing resources under controlled operational costs. It is estimated that around 50% of newly discovered deposits are in the deep-water (between 400 and 1,500 metres) and ultra-deep-water (more than 1,500 metres) range.

- Infrastructure and robotics: Robotics have high potential in the fields of exploitation and maintenance. Oil and gas deposits are exploring the development of subsea completion systems, deployed in the seabed, and managed by underwater robots. These systems are particularly beneficial for deep-water exploitation, as they reduce the need for offshore infrastructure, minimising environmental impacts and costs. Projects like the Chaintest, which received EU funding under the SME-FP6 programme, employ robots to reduce operational costs. For example, a robot that crawls along the chains anchoring platforms to the seabed, performing inspection and maintenance activities. Robotics also play a key part in the possible advance of seabed mining, providing selective and non-intrusive exploitation techniques. As an example of this, the EU funded ROBUST project advanced the development of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle that can hover over the seabed, produce 3-D maps, and analyse resources, using laser technology.

11 Neumann, A. et al. (2021): The role of natural gas in Europe towards 2050. NETI Policy Brief 01/2021, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway.

17EUsalt, 2024. The European Sea Salt Industry - Navigating Production, Trends and Prospects.

18Salt Market Information & Salt Research + Consulting. Report on the European Sea Salt Sector and Outlook. 29 March 2024.

19Salt Market Information & Salt Research + Consulting. Report on the European Sea Salt Sector and Outlook. 29 March 2024.

20Data provided by EUsalt, originating from a survey commissioned to Salt Research + Consulting and Salt Market Information.

21Schlag, S. and Götzfried, F. 2024. Report on the European Sea Salt Sector and Outlook. March 29, 2024.

25 Technical Study: MSP as a tool to support Blue Growth. Sector Fiche: Oil and Gas, Final Version: 16.02.2018, https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/media/document/12243

26 Blue Growth Scenarios and drivers for Sustainable Growth from the Oceans, Seas and Coasts, 2012, https://maritime-forum.ec.europa.eu/document/download/dd6e0bfd-bd35-44f4-9a44-603190abbd31_en?filename=Blue%20Growth%20Final%20Report%2013092012.pdf